The Kafka Dilemma

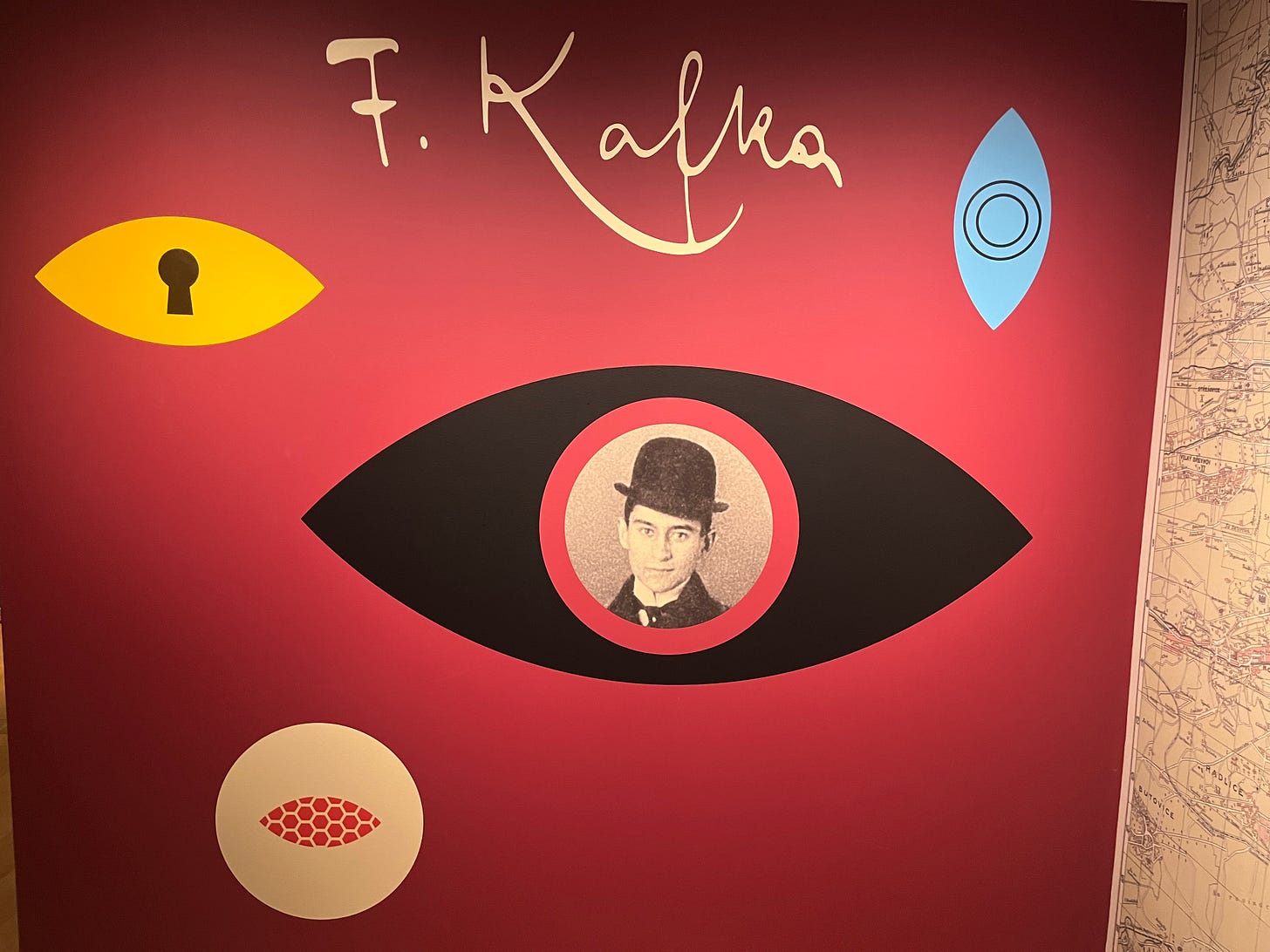

A new exhibit at the Morgan Library fills in some gaps on the elusive author

Franz Kafka is part of a select group of writers whose name is synonymous with an artistic style. “Kakfa-esque” films can include Stanley Kubrick’s “Eyes Wide Shut,” where the Tom Cruise character is plunged into a surreal middle-of-the-night masked orgy, and “Monsieur Klein,” the 1976 Joseph Losey movie set in occupied France in which the protagonist is mistakenly identified as Jewish and desperately tries to stop the walls from closing in.

Besides characterizing scenarios that are dark or strange, “Kafka-esque” may be employed as a colorful way to describe a fruitless encounter with an impermeable bureaucracy. The author might come to mind when navigating a multifaceted nest of phone trees, Siri bots and insurance jargon while attempting to contest a medical bill. I have heard the term “Kafka-esque” often enough, but had not gone back to the source itself since “The Metamorphosis,” which I read in high school and which has been scrambled in my mind with the David Cronenberg movie, “The Fly.”

In anticipation of the Morgan Library’s new exhibit on Kafka, I decided to finally read “The Trial” a few weeks back. Having been conditioned by the cryptic films mentioned above, I found the novel less comprehensively dark than I expected. There are certainly notes of ominousness throughout “The Trial” and at its grim conclusion, but also much humor, as Joseph K. encounters a rogue’s gallery of oddballs, while he tries to navigate one obstacle after another. The men and women who populate this universe appear to accept a code of unwritten rules that seems systematic but which apparently has no fundamental purpose other than self-perpetuation. The protagonist’s behavior is also a mystery. When we first meet him, Joseph K. seems more perturbed that the agents who arrest him ate his breakfast than by the vague, unnamed criminal charges that he seems, on some level, to have been anticipating. He behaves erratically and demonstrates pettiness as he tries to one up the other person in a series of encounters that often feel like confrontations. How much of “The Trial” is meant to be events in a narrative of a “real” story, as opposed to something playing out in the protagonist’s mind?

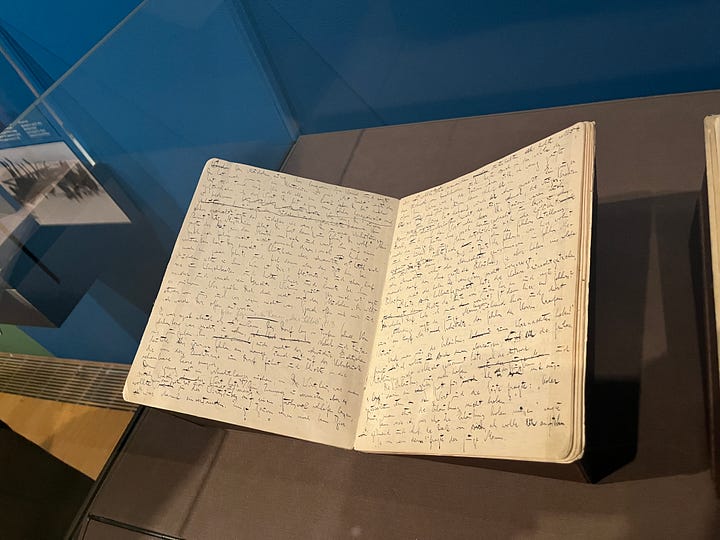

The Morgan Library’s exhibit doesn’t feature significant textual analysis of “The Trial” or Kafka’s other works, yet still manages to challenge some widely-held assumptions that float around the Czech writer, who shot to prominence in the post-World War II period decades after his 1924 passing. The show consists of hand-scrawled writer notebooks, correspondence and other personal items that provide a window into Kafka the man. There are also art pieces and book covers evoking the author and his mysterious works.

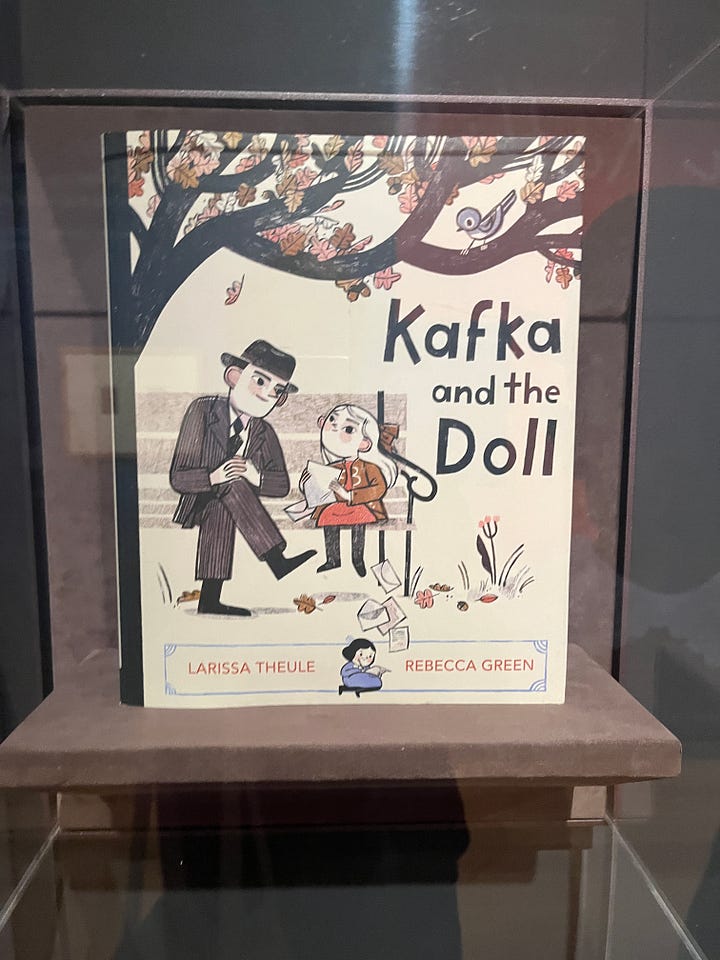

The exhibit undermines the image of the slightly-built author as a lonely figure estranged from an off-putting society. Among the items shown are a children’s book riffing on an encounter between Kafka and a little girl who lost her doll in a park; Kafka then sent letters to the girl in the voice of the doll recounting its voyages. There is also a photograph of Kafka, flanked by shepherd canine and a Prague barmaid. A version of the photo was published on the cover of a book “Lonely, like Franz Kafka,” cropping out the woman and the dog. “The image of Kafka as ‘an unhappy single man’ persists to this day,” reads a caption in the show.

We see postcards in which Kafka playfully bantered with his favorite sister Ottla, recounting satisfying trips to Italy and France; other items give a window into Kafka’s personal quirks: his meticulous approach to exercising, his vegetarianism, highly unusual in his lifetime, and his disdain for noise, a kryptonite to the creative reflection that fueled his fiction. We also learn about Kafka’s curiosity about his Jewish identity as he examined what it meant to him.

The writer lived in obscurity and appears to have liked it that way. But before he died of tuberculosis, Kafka bequeathed three unfinished novels and other writings to friend Max Brod with instructions — obviously not followed — to burn the manuscripts. Brod maintained that he honored the author’s authentic wishes, because if he had truly wanted the works destroyed, Kafka would have done it himself or left them to someone else.

Trained as an attorney, Kafka was skilled in his role at a government workplace safety agency, but viewed the day job as a distraction from his true calling: writing, which he did at night after returning from the office. That process seems to have contributed to a lightness of spirit apparent in photos of a grinning Kafka with Ottla and others interspersed throughout the show.

Even though he died in 1924, Kafka’s life feels bound up with subsequent tragedies befalling the Czech Republic and Europe. Ottla and Kafka’s other sisters were rounded up and killed in World War II after the Nazis invaded the Czech Republic, a period followed by the grim decades under Soviet control. A dilemma is how much to view Kafka’s unwieldy bureaucracies as something to be spoofed as opposed to something much more sinister. “The Trial” can be read as a rumination on this question, or as a story about how a dysfunctional labyrinth of red tape can evolve into something malignant. The latter feels resonant at the moment as dark forces with a hidden agenda seize the levers of administrative power in Washington.